Beautiful Blood on Your

Lip

Successors to GWG

Reviews

“Gun Crazy” (2002)

Seemingly inspired by the conventions of “Spaghetti

Westerns,” Atsushi Muroga’s “Gun Crazy, Episode 1: A Woman from Nowhere”

(“Fukushuu No Kouya”) features the familiar figure of a lone vengeance-seeker

who rides into a frontier town seeking a confrontation with a notorious

bandit. Other familiar genre elements include a stranger with no

background who registers at a seedy hotel before staging a confrontation

in a saloon and recruiting the assistance of a colorful but violence-shy

local character. Genre analysis is put to the test here. Is

“Gun Crazy” actually an anachronistic “Eastern Western” set in 2002 Okinawa?

A self-referential amalgam of Western, Yakuza

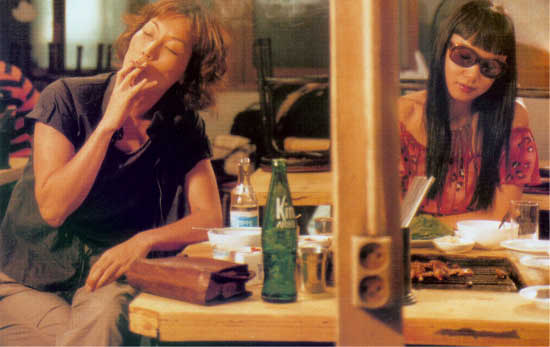

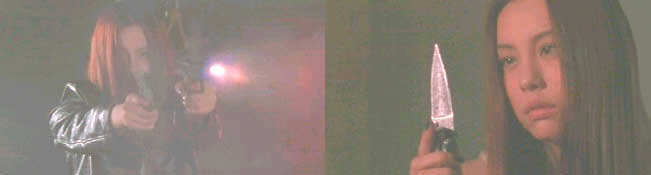

and GWG action film conventions, “A Woman from Nowhere” stars Ryoko Yonekura

as “Saki,” a two-fisted shooter who packs a pair of 9 mm automatics and

arrives astride a Harley-Davidson. The lawless frontier in

this instance is provided by the intertwined civilian and military base

culture of Okinawa, complete with washed-up alcoholic town cop (Shun Sugata).

Yonekura’s character “Saki” is visually stunning – beautiful yet ambiguous.

In addition to leathers and knee-high motorcycle boots she also has an

articulated brace on her left leg, and whimpers when an American soldier

gropes that leg in a bar. Yonekura manages to be convincingly tough

without also being a parody. When shot, “Saki” goes down. When

kicked, she folds up. When struck and stamped on, she bruises and

bleeds.

A self-referential amalgam of Western, Yakuza

and GWG action film conventions, “A Woman from Nowhere” stars Ryoko Yonekura

as “Saki,” a two-fisted shooter who packs a pair of 9 mm automatics and

arrives astride a Harley-Davidson. The lawless frontier in

this instance is provided by the intertwined civilian and military base

culture of Okinawa, complete with washed-up alcoholic town cop (Shun Sugata).

Yonekura’s character “Saki” is visually stunning – beautiful yet ambiguous.

In addition to leathers and knee-high motorcycle boots she also has an

articulated brace on her left leg, and whimpers when an American soldier

gropes that leg in a bar. Yonekura manages to be convincingly tough

without also being a parody. When shot, “Saki” goes down. When

kicked, she folds up. When struck and stamped on, she bruises and

bleeds.

“Saki’s” erratic vengeance mission at times courts

suicide. In one of the film’s best scenes, “Saki” is pawed and propositioned

by two American soldiers in a bar. After delivering several punishing

kicks, “Saki” beats them to the draw with a pair of 9 mm automatics in

a spring-loaded rig concealed in her coat sleeves. The slow motion

gunfire is as good as the genre gets. In another interesting sequence,

“Saki” dumps the bloody body of another heavily wounded American soldier

(a Japanese-American played by Takeshi Yamato) into the back of a pickup,

along with two suitcases of illegal cash stolen from the U.S. base.

Political undertones concerning the ambiguous Japanese perspective on the

continuing U.S. military occupation (the setting is in Japan but is not

a part of Japan, as one character puts it) alternate with Yonekura’s unusual

and sometimes incongruous facial expressions.

“Saki’s” erratic vengeance mission at times courts

suicide. In one of the film’s best scenes, “Saki” is pawed and propositioned

by two American soldiers in a bar. After delivering several punishing

kicks, “Saki” beats them to the draw with a pair of 9 mm automatics in

a spring-loaded rig concealed in her coat sleeves. The slow motion

gunfire is as good as the genre gets. In another interesting sequence,

“Saki” dumps the bloody body of another heavily wounded American soldier

(a Japanese-American played by Takeshi Yamato) into the back of a pickup,

along with two suitcases of illegal cash stolen from the U.S. base.

Political undertones concerning the ambiguous Japanese perspective on the

continuing U.S. military occupation (the setting is in Japan but is not

a part of Japan, as one character puts it) alternate with Yonekura’s unusual

and sometimes incongruous facial expressions.

Yonekura’s performance spans the range of negative

emotions, but has a compelling edge of real instability. Smiling

while fingering a combat knife, frowning in perplexity at the consequences

of her rashness, she presents a figure whose intense oddness is finally

traced to a horrific childhood murder 15 years before. As a little

girl, “Saki” is placed in the driver’s seat of a truck that will tear apart

her policeman father if she releases the brake. This is rendered

inevitable by vicious mutilation of her leg, so the young “Saki” is forced

to give in to pain and physical weakness. She subsequently experiences

amputation and fitting of a prosthetic leg, and later appears to have considered

suicide. The adult “Saki” is definitely not an individual to be casually

groped in a bar.

Yonekura’s performance spans the range of negative

emotions, but has a compelling edge of real instability. Smiling

while fingering a combat knife, frowning in perplexity at the consequences

of her rashness, she presents a figure whose intense oddness is finally

traced to a horrific childhood murder 15 years before. As a little

girl, “Saki” is placed in the driver’s seat of a truck that will tear apart

her policeman father if she releases the brake. This is rendered

inevitable by vicious mutilation of her leg, so the young “Saki” is forced

to give in to pain and physical weakness. She subsequently experiences

amputation and fitting of a prosthetic leg, and later appears to have considered

suicide. The adult “Saki” is definitely not an individual to be casually

groped in a bar.

The rest of the narrative plays out as a yakuza

actioner, involving a series of bloody and well-choreographed slow-motion

gunfights. By the final scene, “Saki” has been shot, battered and

has had her artificial limb shot off. However, in an ultimately symbolic

act of retribution, she uses both the knife that mutilated her as a child

and a rocket launcher concealed in her prosthetic limb to exact vengeance

on the yakuza “Tojo” (Shingo Tsurumi) who killed her father. At their

final face off, he sneeringly taunts her with responsibility for killing

her own father, and even suggests she should be glad she lost the limb

responsible for his death, since she must have hated this part of her body.

But in the end, true vengeance is actually dispensed by a disabled person

– and is made possible by the disability itself.

The rest of the narrative plays out as a yakuza

actioner, involving a series of bloody and well-choreographed slow-motion

gunfights. By the final scene, “Saki” has been shot, battered and

has had her artificial limb shot off. However, in an ultimately symbolic

act of retribution, she uses both the knife that mutilated her as a child

and a rocket launcher concealed in her prosthetic limb to exact vengeance

on the yakuza “Tojo” (Shingo Tsurumi) who killed her father. At their

final face off, he sneeringly taunts her with responsibility for killing

her own father, and even suggests she should be glad she lost the limb

responsible for his death, since she must have hated this part of her body.

But in the end, true vengeance is actually dispensed by a disabled person

– and is made possible by the disability itself.

Although not distinguished by particularly high

or sophisticated production values, “Gun Crazy, Episode 1” is nevertheless

competently filmed with some interesting location shooting and good close-ups.

Muroga provides glimpses of the past, but stays his hand until the end

before revealing “Saki’s” secret. The martial arts choreography and

use of wirework may be weaknesses, but the gunplay is among the best of

this genre in use of slow motion effects. During the final face-off

it is unclear whether the scene more closely resembles a Western gunfight

or prelude to a clash of samurai. “A Woman from Nowhere” is the first

in a series, and is easily the best of the four titles released so far.

Its relatively short running time of 67 minutes contributes to dramatic

pacing.

Although not distinguished by particularly high

or sophisticated production values, “Gun Crazy, Episode 1” is nevertheless

competently filmed with some interesting location shooting and good close-ups.

Muroga provides glimpses of the past, but stays his hand until the end

before revealing “Saki’s” secret. The martial arts choreography and

use of wirework may be weaknesses, but the gunplay is among the best of

this genre in use of slow motion effects. During the final face-off

it is unclear whether the scene more closely resembles a Western gunfight

or prelude to a clash of samurai. “A Woman from Nowhere” is the first

in a series, and is easily the best of the four titles released so far.

Its relatively short running time of 67 minutes contributes to dramatic

pacing.

At the end, her mission completed, a repaired

“Saki” mounts her Harley and disappears up the causeway. Other Japanese

GWG films often do not live up to their promise and are vitiated by gratuitous

exploitation elements. “A Woman from Nowhere” wisely stays very close

to the GWG action formula and may be one of the best of its type.

Yonekura has the stature, physical conditioning and exercise-honed flexibility

to engage in some convincing action sequences. But it is her acting

– especially her offbeat facial expressions – more than the kicks and pistols,

that delivers the real visual pleasure.

At the end, her mission completed, a repaired

“Saki” mounts her Harley and disappears up the causeway. Other Japanese

GWG films often do not live up to their promise and are vitiated by gratuitous

exploitation elements. “A Woman from Nowhere” wisely stays very close

to the GWG action formula and may be one of the best of its type.

Yonekura has the stature, physical conditioning and exercise-honed flexibility

to engage in some convincing action sequences. But it is her acting

– especially her offbeat facial expressions – more than the kicks and pistols,

that delivers the real visual pleasure.

“H: Murmurs” (2002)

“Mi-Yun Kim,” superbly played by Jung-ah Yum,

is the lead investigator into a series of gruesome murders of young women.

Yum’s acting skill layers empathy, sadness, hatred and the cumulative effects

of catastrophic loss behind “Detective Kim’s” resolutely deadpan exterior.

Her passion is cold, snuffed out by dangerously controlled anger.

As theories of motive multiply with the bodies, “Kim” painstakingly deciphers

the gory gynecologic symbolism of the killer’s acts. His crimes mysteriously

seem to recapitulate those of an already-convicted killer, “Hyun Shin”

(Seung-woo Cho), now on death row.

Director Jong-hyuk Lee slowly reveals that this

individual has enacted an exquisitely organized continuation of his crimes

via hypnotic influence. Although the science behind this may be junk,

the cast delivers powerfully credible performances. In their desperation

to prevent more killings, the police investigators resort to rougher tactics.

But even after the last suspect has committed suicide and the convicted

murderer “Shin” has been executed, the killing continues.

Director Jong-hyuk Lee slowly reveals that this

individual has enacted an exquisitely organized continuation of his crimes

via hypnotic influence. Although the science behind this may be junk,

the cast delivers powerfully credible performances. In their desperation

to prevent more killings, the police investigators resort to rougher tactics.

But even after the last suspect has committed suicide and the convicted

murderer “Shin” has been executed, the killing continues.

A terrible ambiguity pervades the entire investigation.

One of “Kim’s” men, “Detective Kang” (Jin-hee Ji) is strangely present

– or absent – at crime scenes. “Kim” is almost killed after discovering

the body of “Shin’s” former therapist. As “Kim” discovers the origins

of “Shin’s” fear and hatred of women, she also grasps – too late – the

secret of his influence from a prison cell, as well as the identity of

the actual killer. In front of the astonished gaze of her other investigator,

“Kim” calmly smokes a final cigarette before equally calmly executing the

suspect.

A terrible ambiguity pervades the entire investigation.

One of “Kim’s” men, “Detective Kang” (Jin-hee Ji) is strangely present

– or absent – at crime scenes. “Kim” is almost killed after discovering

the body of “Shin’s” former therapist. As “Kim” discovers the origins

of “Shin’s” fear and hatred of women, she also grasps – too late – the

secret of his influence from a prison cell, as well as the identity of

the actual killer. In front of the astonished gaze of her other investigator,

“Kim” calmly smokes a final cigarette before equally calmly executing the

suspect.

Jung-Ah Yum is herself hypnotic as the driven,

tightly wrapped “Inspector Kim.” She veers between icy determination

and moments of all-too-human hesitation before rounding a corner to confront

the unknown. Sometimes it seems unclear whether “Kim” may ultimately

use her weapon on someone else or herself. The internal fracture

in the character of “Kim” quietly bleeds sadness as the chase ricochets

through a claustrophobic maze of urban alleyways, fetid apartments and

dank building hallways. The film opens in a dark, rain sodden garbage

dump and closes on a bright expanse of sunlit beach. The sunlight,

however, fails to dispel the effects of contact with the dark abyss that

has confronted the survivors.

Jung-Ah Yum is herself hypnotic as the driven,

tightly wrapped “Inspector Kim.” She veers between icy determination

and moments of all-too-human hesitation before rounding a corner to confront

the unknown. Sometimes it seems unclear whether “Kim” may ultimately

use her weapon on someone else or herself. The internal fracture

in the character of “Kim” quietly bleeds sadness as the chase ricochets

through a claustrophobic maze of urban alleyways, fetid apartments and

dank building hallways. The film opens in a dark, rain sodden garbage

dump and closes on a bright expanse of sunlit beach. The sunlight,

however, fails to dispel the effects of contact with the dark abyss that

has confronted the survivors.

“No Blood No Tears” (2002)

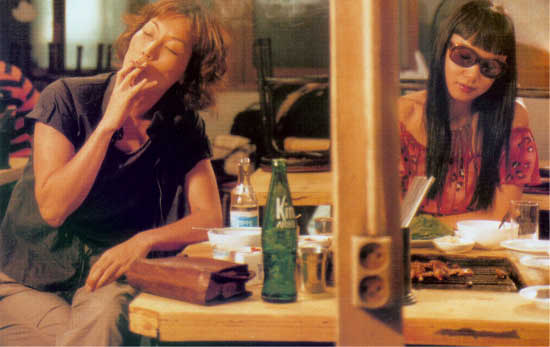

The betrayal and ambiguity of “Bound” intersect

with the distinctive narrative conventions of “Memento” in this intriguing

women’s friendship film that director Seung-Wan Ryu has described as “pulp

noir.” Noir elements include extensive use of contrast and deep shadow

as well as betrayal and plot complexity. Hye-young Lee plays a world-weary

cab driver “Gyung-sun” who struggles to make ends meet to pay off her ex-husband’s

gambling debt. Living alone in meager surroundings and separated

from her daughter, “Gyung-sun” has to fend off the malevolent and occasionally

violently abusive attention of drunken fares, loan sharks and the police.

Her marginal existence literally collides, in the form of a traffic accident,

with that of the equally desperate “Soo-jin” (Do-yeon Jun) who is being

relentlessly battered by her ex-boxer boyfriend “Puldok” (Jae-Yeong Jeong).

After “Gyung-sun” stands up to him at the accident scene, “Soo-jin” is

impressed by her stand and seeks her out.

Gradually, the two women form a tentative bond

marked by shared adversity but mutual suspicion – “Soo-jin” an aspiring

singer controlled by an abusive boyfriend and a scar on her face, and “Gyung-sun”

by ever-present risk of arrest or worse associated with a criminal past

in her character’s backstory. When “Soo-jin” suggests an elaborate

scam to steal the sizeable proceeds of her boyfriend’s illegal dogfighting

operation, “Gyung-sun” initially refuses but is driven to change her mind

after another beating by loan sharks. Violence against women is foregrounded

in a withering critique of abusive male behavior and patriarchal norms

throughout the film. The opening scene of leering, groping entitlement

of a drunken fare in “Gyung-sun’s” cab, “Puldok’s” beatings and verbal

abuse, a scene of domestic violence in a family-run restaurant, and the

casual

brutality of every male character all implicate the abuse of power by men.

Even the investigating police detective relies on intimidation and coercion,

ultimately falling into the same pattern of control. As “Gyung-sun”

says, “Pretending to be a kind old man to get info was disgusting.”

Gradually, the two women form a tentative bond

marked by shared adversity but mutual suspicion – “Soo-jin” an aspiring

singer controlled by an abusive boyfriend and a scar on her face, and “Gyung-sun”

by ever-present risk of arrest or worse associated with a criminal past

in her character’s backstory. When “Soo-jin” suggests an elaborate

scam to steal the sizeable proceeds of her boyfriend’s illegal dogfighting

operation, “Gyung-sun” initially refuses but is driven to change her mind

after another beating by loan sharks. Violence against women is foregrounded

in a withering critique of abusive male behavior and patriarchal norms

throughout the film. The opening scene of leering, groping entitlement

of a drunken fare in “Gyung-sun’s” cab, “Puldok’s” beatings and verbal

abuse, a scene of domestic violence in a family-run restaurant, and the

casual

brutality of every male character all implicate the abuse of power by men.

Even the investigating police detective relies on intimidation and coercion,

ultimately falling into the same pattern of control. As “Gyung-sun”

says, “Pretending to be a kind old man to get info was disgusting.”

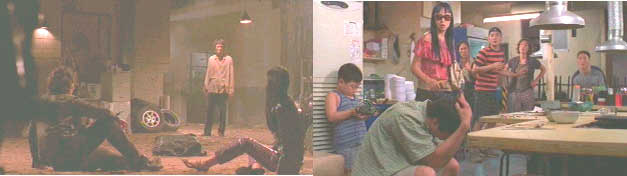

The film also explores the ways in which such

coercive assumptions corrupt women’s relations even with each other.

When “Soo-jin” builds some additional layers of protection into her plot

to steal the money and mislead various partners, “Gyung-sun” is all too

easily persuaded that her new partner has eloped with one of her boyfriend’s

henchmen. It is only after the two women fight – nearly draining

each other’s strength in a dangerously premature confrontation – that the

misunderstanding and the real threat are discovered. “Puldok”, bleeding

and battered from an earlier confrontation with gang members and the police,

staggers into the garage where “Soo-jin” and “Gyung-sun” have met.

This time his vicious assumptions prove fatal as he delivers a final beating

to both women. When “Soo-jin” finally reacts, the camera provides

a close-up of her tightening fist before she counter-attacks. “Puldok’s”

torrent of verbal and physical abuse spurs “Gyung-sun” to a final superhuman

effort, fueled by accumulated rage. She stabs him in the neck with

a car key. This scene, shot in a muddy, broken-down garage with rain

pouring in, culminates in a life-and-death struggle between sweating, bleeding,

battered protagonists who are soaked and filthy. As “Puldok’s” carotid

blood sprays into the rain and he finally collapses in the mire, “Soo-jin”

and “Gyung-sun” can only watch exhausted as the money is taken by a petty

criminal – a bartender and police informant – who has been following them.

The film also explores the ways in which such

coercive assumptions corrupt women’s relations even with each other.

When “Soo-jin” builds some additional layers of protection into her plot

to steal the money and mislead various partners, “Gyung-sun” is all too

easily persuaded that her new partner has eloped with one of her boyfriend’s

henchmen. It is only after the two women fight – nearly draining

each other’s strength in a dangerously premature confrontation – that the

misunderstanding and the real threat are discovered. “Puldok”, bleeding

and battered from an earlier confrontation with gang members and the police,

staggers into the garage where “Soo-jin” and “Gyung-sun” have met.

This time his vicious assumptions prove fatal as he delivers a final beating

to both women. When “Soo-jin” finally reacts, the camera provides

a close-up of her tightening fist before she counter-attacks. “Puldok’s”

torrent of verbal and physical abuse spurs “Gyung-sun” to a final superhuman

effort, fueled by accumulated rage. She stabs him in the neck with

a car key. This scene, shot in a muddy, broken-down garage with rain

pouring in, culminates in a life-and-death struggle between sweating, bleeding,

battered protagonists who are soaked and filthy. As “Puldok’s” carotid

blood sprays into the rain and he finally collapses in the mire, “Soo-jin”

and “Gyung-sun” can only watch exhausted as the money is taken by a petty

criminal – a bartender and police informant – who has been following them.

Seemingly now released from the presence of the

money and threat of pursuit, “Soo-jin” and “Gyung-sun” contemplate their

fate in the harsh light of day, seated side by side on a nearly deserted

beach nursing their injuries. In adversity they have found both common

cause and ironic mutual appreciation, and commit to jointly open a restaurant.

Within the narrative conventions of Asian cinema this represents a powerful

affirmation of bonding, solidarity and normalcy – an approximation to “happy

ever after.” “Soo-jin” still talks about becoming a singer, but now

“Gyung-sun” may become her manager. These are among several subtle

indicators that “Gyung-sun” might well replace “Puldok” in “Soo-jin’s”

life. “Gyung-sun” cuts an androgynous figure in her taxi driver’s

uniform, pants and work shoes. She displays resilience and courage

while fighting for “Soo-jin” as well as jealous ruthlessness in slaying

“Soo-jin’s” boyfriend in front of her in a scene of primal implications.

These matters settled she at last plans to re-unite with her daughter.

The film’s final scene appears conclusive. After “Soo-jin” and “Gyung-sun”

lay their plans for a new life together, the camera pans to a close-up

of “Soo-jin’s" car keys – the instrument of “Gyung-sun’s” murderous power

– and lingers on a key ring photograph of “Soo-jin” and her former boyfriend.

Seemingly now released from the presence of the

money and threat of pursuit, “Soo-jin” and “Gyung-sun” contemplate their

fate in the harsh light of day, seated side by side on a nearly deserted

beach nursing their injuries. In adversity they have found both common

cause and ironic mutual appreciation, and commit to jointly open a restaurant.

Within the narrative conventions of Asian cinema this represents a powerful

affirmation of bonding, solidarity and normalcy – an approximation to “happy

ever after.” “Soo-jin” still talks about becoming a singer, but now

“Gyung-sun” may become her manager. These are among several subtle

indicators that “Gyung-sun” might well replace “Puldok” in “Soo-jin’s”

life. “Gyung-sun” cuts an androgynous figure in her taxi driver’s

uniform, pants and work shoes. She displays resilience and courage

while fighting for “Soo-jin” as well as jealous ruthlessness in slaying

“Soo-jin’s” boyfriend in front of her in a scene of primal implications.

These matters settled she at last plans to re-unite with her daughter.

The film’s final scene appears conclusive. After “Soo-jin” and “Gyung-sun”

lay their plans for a new life together, the camera pans to a close-up

of “Soo-jin’s" car keys – the instrument of “Gyung-sun’s” murderous power

– and lingers on a key ring photograph of “Soo-jin” and her former boyfriend.

The symbolism of photographs to convey relationship

messages is foreshadowed earlier in the film. While “Soo-jin” contemplates

the betrayal of her affection and loyalty, there is a montage of photographs

from happier days with views of her boyfriend snoring on the sofa or sitting

on the toilet. “Gyung-sun’s” use of a key as a weapon is also anticipated

in a previous fight with loan sharks, while additional associations between

keys and autonomous action are suggested by “Gyung-sun’s” hotwiring a car

(after looking for a key) to follow “Soo-jin.”

The symbolism of photographs to convey relationship

messages is foreshadowed earlier in the film. While “Soo-jin” contemplates

the betrayal of her affection and loyalty, there is a montage of photographs

from happier days with views of her boyfriend snoring on the sofa or sitting

on the toilet. “Gyung-sun’s” use of a key as a weapon is also anticipated

in a previous fight with loan sharks, while additional associations between

keys and autonomous action are suggested by “Gyung-sun’s” hotwiring a car

(after looking for a key) to follow “Soo-jin.”

Although in parts an action comedy, the comic

elements serve mainly to disrupt the action narrative in accordance with

pause-burst-pause conventions of Asian action cinema. Comic elements

also ridicule many stock elements of these same conventions, and heighten

contrast with the grim action scenes. Du-Hong Jeong shines as a lethal

enforcer who speaks not a single line of dialog. Overall, this is

an engaging and occasionally moving work with solid production values,

excellent acting by the leads and a strong social message backed up by

layers of intrigue and symbolism.

Although in parts an action comedy, the comic

elements serve mainly to disrupt the action narrative in accordance with

pause-burst-pause conventions of Asian action cinema. Comic elements

also ridicule many stock elements of these same conventions, and heighten

contrast with the grim action scenes. Du-Hong Jeong shines as a lethal

enforcer who speaks not a single line of dialog. Overall, this is

an engaging and occasionally moving work with solid production values,

excellent acting by the leads and a strong social message backed up by

layers of intrigue and symbolism.