A Place of Rage

“Man is such a worthless animal” (Miho Kanno,

“Tomie”)

Hideyuki Hirayama’s “Out” (2002) illustrates

how mise-en-scene – perhaps even more than narrative – establishes genre.

Natsuo Kirino’s angry feminist crime novel, on which the film is based,

depicts four women who are spiritually broken on the wheel of patriarchal

power and indifference. They work the night shift in a run-down boxed

lunch factory in a blighted industrial neighborhood. These women

work nights both for the shift differential and to escape their families.

Their shabby residences reflect their social marginalization as the victims

of gender and age discrimination or downsizing. The shadow figures

of Kirino’s novel come to life through the radical and horrifying acts

of participation in murder, dismemberment and abandonment of family – blatant

violations of fundamental social norms. A faithful cinematic realization

of this narrative would involve darkness, poverty, aging, exhaustion, exploitation

and cruel disappointment, in addition to the gory symbolism of the dismembered

body.

But Hirayama’s film transforms these desperately

secret lives into a series of encounters between smiling, well dressed

women who inhabit bright, airy homes and work in a spotlessly gleaming

high-tech factory – far removed from the stifling tatami rooms of the novel.

The film’s cinematic emphasis on brilliant skies and well-lit spaces suggests

anything but horror. The business of cutting up bodies – ankle deep

in blood and steaming intestines – is virtually excised from the film.

Instead it is conducted largely off-camera by the protagonists wearing

white plastic protective gear that both reassuringly suggests surgical

garb and makes them seem anonymous. The merest hint of blood connotes

surgery rather than butchery, and the film discreetly avoids lingering

on images that might otherwise code its female protagonists as monstrous

– such as the lead character “Masako Katori” (Mieko Harada) cutting off

people’s heads. Yet this betrays the narrative power of the novel

that invites identification with “Masako” strong enough to sustain sympathy

for her monstrous acts. The film also transforms her friend “Yayoi

Yamamoto” (Naomi Nishida) into the heavily pregnant wife of a partner abuser

who kills her husband in self-defense – rather than because she’s had enough

of him as in the book. Her character’s pregnancy in the film seems

a device to garner sympathy. It may be acceptable to kill in defense

of one’s unborn child, and her character’s demeanor seems to convey regret.

But this misses the dark heart of Kirino’s novel where “Yayoi” wasn’t pregnant,

and had simply had enough of her husband. She actually found it thrilling

and liberating to kill him, and when “Masako” kills another man it becomes

evident that the “beast” they have awoken is in themselves.

But Hirayama’s film transforms these desperately

secret lives into a series of encounters between smiling, well dressed

women who inhabit bright, airy homes and work in a spotlessly gleaming

high-tech factory – far removed from the stifling tatami rooms of the novel.

The film’s cinematic emphasis on brilliant skies and well-lit spaces suggests

anything but horror. The business of cutting up bodies – ankle deep

in blood and steaming intestines – is virtually excised from the film.

Instead it is conducted largely off-camera by the protagonists wearing

white plastic protective gear that both reassuringly suggests surgical

garb and makes them seem anonymous. The merest hint of blood connotes

surgery rather than butchery, and the film discreetly avoids lingering

on images that might otherwise code its female protagonists as monstrous

– such as the lead character “Masako Katori” (Mieko Harada) cutting off

people’s heads. Yet this betrays the narrative power of the novel

that invites identification with “Masako” strong enough to sustain sympathy

for her monstrous acts. The film also transforms her friend “Yayoi

Yamamoto” (Naomi Nishida) into the heavily pregnant wife of a partner abuser

who kills her husband in self-defense – rather than because she’s had enough

of him as in the book. Her character’s pregnancy in the film seems

a device to garner sympathy. It may be acceptable to kill in defense

of one’s unborn child, and her character’s demeanor seems to convey regret.

But this misses the dark heart of Kirino’s novel where “Yayoi” wasn’t pregnant,

and had simply had enough of her husband. She actually found it thrilling

and liberating to kill him, and when “Masako” kills another man it becomes

evident that the “beast” they have awoken is in themselves.

By constructing the murder of “Yayoi’s” husband

as self-defense and avoiding giving the female protagonists an active cinematic

gaze, key cinematic signifiers are aligned with other elements such as

bright, spacious surroundings and clinical, white garb to collectively

soften and deflect the impact of these women’s acts. While the novel

can easily be read as horror, Hirayama’s film adaptation adopts the gentler

mantle of drama. Such divergence offers an opportunity to note certain

conventions of genre cinema. Drama – as a “higher” genre than horror

– is positioned to offer social commentary but is simultaneously constrained

by conventions of taste. The “lower” genre of horror may actually

be better equipped to bluntly confront the troubling themes of gender,

power and desire that are often deeply buried in other texts.

By constructing the murder of “Yayoi’s” husband

as self-defense and avoiding giving the female protagonists an active cinematic

gaze, key cinematic signifiers are aligned with other elements such as

bright, spacious surroundings and clinical, white garb to collectively

soften and deflect the impact of these women’s acts. While the novel

can easily be read as horror, Hirayama’s film adaptation adopts the gentler

mantle of drama. Such divergence offers an opportunity to note certain

conventions of genre cinema. Drama – as a “higher” genre than horror

– is positioned to offer social commentary but is simultaneously constrained

by conventions of taste. The “lower” genre of horror may actually

be better equipped to bluntly confront the troubling themes of gender,

power and desire that are often deeply buried in other texts.

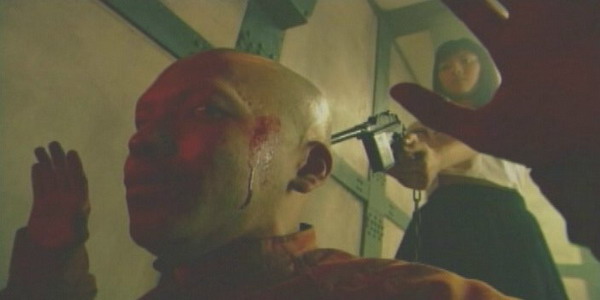

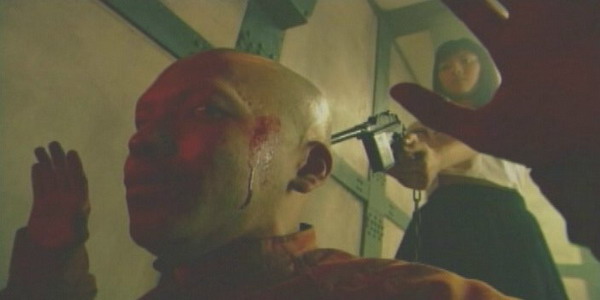

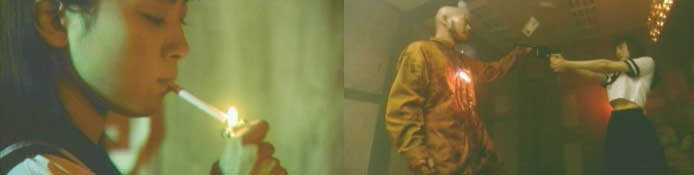

Hiroki Yamaguchi’s “Gusha no bindume” (“Hellevator:

The Bottled Fools,” 2004) is everything “Out” should have been. Yamaguchi’s

film blends elements of horror with science fiction set in a parallel society,

culminating in a narrative resolution comparable to that of “Avalon.”

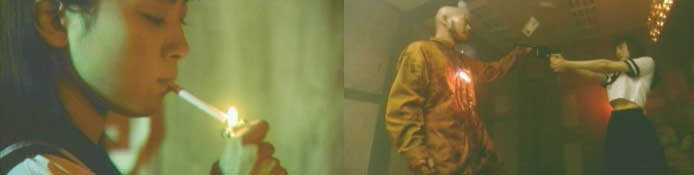

Luchino Fujisaki plays an eponymous 17-year-old schoolgirl attired in the

classic sailor suit and loose leg warmers so frequently fetishized in Japanese

cinema. Her blankly beautiful appearance and insouciant manner are

a thin veneer over casual violence and rage of psychotic intensity.

While her appearance may seem markedly incongruous in the dark urban dystopia

of the claustrophobic, vertical mega-city of Yamaguchi’s imaginings, “Fujisaki”

shocks even its twisted denizens with her brutality as she causes an explosion

that kills 113 people with a casually discarded cigarette, empties the

clip of a Mauser automatic pistol into a convicted murderer in gratuitously

bloody slow motion, and eviscerates a male microbiologist.

Hiroki Yamaguchi’s “Gusha no bindume” (“Hellevator:

The Bottled Fools,” 2004) is everything “Out” should have been. Yamaguchi’s

film blends elements of horror with science fiction set in a parallel society,

culminating in a narrative resolution comparable to that of “Avalon.”

Luchino Fujisaki plays an eponymous 17-year-old schoolgirl attired in the

classic sailor suit and loose leg warmers so frequently fetishized in Japanese

cinema. Her blankly beautiful appearance and insouciant manner are

a thin veneer over casual violence and rage of psychotic intensity.

While her appearance may seem markedly incongruous in the dark urban dystopia

of the claustrophobic, vertical mega-city of Yamaguchi’s imaginings, “Fujisaki”

shocks even its twisted denizens with her brutality as she causes an explosion

that kills 113 people with a casually discarded cigarette, empties the

clip of a Mauser automatic pistol into a convicted murderer in gratuitously

bloody slow motion, and eviscerates a male microbiologist.

The driving force, seen in flashbacks whose repetition

captures their unending influence, is her legacy of physical and sexual

abuse by her father – ultimately butchered by “Luchino” with a pair of

shears. Although initially presented within the text as psychic,

“Fujisaki” actually appears psychotic. Her mind reading and mental

transparency result in classic paranoid imaginings of plots and secret

surveillance. “Fujisaki” slays the microbiologist under influence

of perceived mind control by a punk kid slumped on the floor of the massive

elevator where most of the film is set. In her imaginings he is an

undercover agent for the ubiquitous surveillance bureau, while the microbiologist

is about to unleash a viral weapon contained in a jar with a genetically

altered fetus. As she kills him, the jar rolls away spilling its

actual content of heart medications. Earlier, she suggestively imagines

that the woman with a baby carriage who is in the elevator has actually

killed her own infant by placing it in a locker.

The driving force, seen in flashbacks whose repetition

captures their unending influence, is her legacy of physical and sexual

abuse by her father – ultimately butchered by “Luchino” with a pair of

shears. Although initially presented within the text as psychic,

“Fujisaki” actually appears psychotic. Her mind reading and mental

transparency result in classic paranoid imaginings of plots and secret

surveillance. “Fujisaki” slays the microbiologist under influence

of perceived mind control by a punk kid slumped on the floor of the massive

elevator where most of the film is set. In her imaginings he is an

undercover agent for the ubiquitous surveillance bureau, while the microbiologist

is about to unleash a viral weapon contained in a jar with a genetically

altered fetus. As she kills him, the jar rolls away spilling its

actual content of heart medications. Earlier, she suggestively imagines

that the woman with a baby carriage who is in the elevator has actually

killed her own infant by placing it in a locker.

At the film’s close, “Fujisaki” is literally saturated

with other people’s blood. Far from saving the people whose lives

briefly come together in the elevator that travels between hundreds of

city levels, she is a heinous criminal. The film’s ultimate irony

is that she is sentenced to “disposal” and is duly delivered to the mysterious

“Level 0” in the orange jumpsuit of those so convicted. Instead of

dying, however, “Fujisaki” has her memories erased and emerges into the

nighttime in central Tokyo, on her own. Having started at the very

bottom, in a community for the mentally ill, “Fujisaki” rides the elevator

all the way to the top.

At the film’s close, “Fujisaki” is literally saturated

with other people’s blood. Far from saving the people whose lives

briefly come together in the elevator that travels between hundreds of

city levels, she is a heinous criminal. The film’s ultimate irony

is that she is sentenced to “disposal” and is duly delivered to the mysterious

“Level 0” in the orange jumpsuit of those so convicted. Instead of

dying, however, “Fujisaki” has her memories erased and emerges into the

nighttime in central Tokyo, on her own. Having started at the very

bottom, in a community for the mentally ill, “Fujisaki” rides the elevator

all the way to the top.

This provocative work can be interpreted on several

levels. Following a tradition traceable through Ridley Scott’s “Blade

Runner” to Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” it presents a compelling vision of

urban dystopia that can easily be read as a metaphor for the woes of contemporary

society. People shuffle endlessly through a claustrophobic transportation

network that seems to have become their primary activity. The vertical

city-state is organized into occupational strata, physically separating

and stigmatizing its citizens. The gulf between a phalanx of identical

salarymen and others – a mother, young people – is unbridgeable.

Surveillance and order are oppressive. Officialdom is sadistic and

arbitrary. The elevator operators – beautiful young women with highly

stylized costumes and gestures reminiscent of mannequins – epitomize the

occupational plight of so many Japanese women.

This provocative work can be interpreted on several

levels. Following a tradition traceable through Ridley Scott’s “Blade

Runner” to Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” it presents a compelling vision of

urban dystopia that can easily be read as a metaphor for the woes of contemporary

society. People shuffle endlessly through a claustrophobic transportation

network that seems to have become their primary activity. The vertical

city-state is organized into occupational strata, physically separating

and stigmatizing its citizens. The gulf between a phalanx of identical

salarymen and others – a mother, young people – is unbridgeable.

Surveillance and order are oppressive. Officialdom is sadistic and

arbitrary. The elevator operators – beautiful young women with highly

stylized costumes and gestures reminiscent of mannequins – epitomize the

occupational plight of so many Japanese women.

This system – itself hellish enough – begins to

break down with the arrival in the transport elevator of two convicted

convicts – a murderer and a rapist-cannibal. With the explosion of

a terrorist bomb they break loose and begin to prey on the occupants of

the elevator. Only three people fight back – “Fujisaki” who is tipped

over the edge by any male advance, the microbiologist who is concerned

to save his money and career, and the female elevator operator who announces

she has been trained to deal with these types of emergencies. The

young man who is present remains alienated even from an existential threat.

These elements starkly present the crushing forces of patriarchal power

that privileges masculinity, rules, money and the subjection of women.

This system – itself hellish enough – begins to

break down with the arrival in the transport elevator of two convicted

convicts – a murderer and a rapist-cannibal. With the explosion of

a terrorist bomb they break loose and begin to prey on the occupants of

the elevator. Only three people fight back – “Fujisaki” who is tipped

over the edge by any male advance, the microbiologist who is concerned

to save his money and career, and the female elevator operator who announces

she has been trained to deal with these types of emergencies. The

young man who is present remains alienated even from an existential threat.

These elements starkly present the crushing forces of patriarchal power

that privileges masculinity, rules, money and the subjection of women.

But this order is ultimately overturned by circumstances

that elicit the most basic of human passions – fear, lust, greed, rage

– the “beasts” of Kirino’s literary “Out.” Although they are the

catalysts, it is not the two convicted murderers who ultimately wreak mayhem.

Instead it is “Luchino Fujisaki” who achieves a blood-drenched climax involving

evisceration every bit as horrible as the crimes of those officially designated

as monstrous. This is social criticism of the most savagely primal

sort. Salarymen, scientists, elevator women, housewives, disaffected

youth and schoolgirls are quickly stripped down to those attributes imposed

on them by roles. Ultimately, all breaks down under the pressure

of extraordinary circumstances. Even the icy elevator lady loses

her composure. “Hellevator” makes no secret of its dystopian vision

or how it stands in relation to contemporary Japanese society, both metaphorically

and literally underneath it.

But this order is ultimately overturned by circumstances

that elicit the most basic of human passions – fear, lust, greed, rage

– the “beasts” of Kirino’s literary “Out.” Although they are the

catalysts, it is not the two convicted murderers who ultimately wreak mayhem.

Instead it is “Luchino Fujisaki” who achieves a blood-drenched climax involving

evisceration every bit as horrible as the crimes of those officially designated

as monstrous. This is social criticism of the most savagely primal

sort. Salarymen, scientists, elevator women, housewives, disaffected

youth and schoolgirls are quickly stripped down to those attributes imposed

on them by roles. Ultimately, all breaks down under the pressure

of extraordinary circumstances. Even the icy elevator lady loses

her composure. “Hellevator” makes no secret of its dystopian vision

or how it stands in relation to contemporary Japanese society, both metaphorically

and literally underneath it.

“Hellevator” seems relatively unusual for a contemporary

Japanese horror film. Its gritty reliance on both emotional and physical

violence and claustrophobic mise-en-scene, seem more reminiscent of the

elemental violations at the finale of “Audition” or cyberpunk excess than

of “Ring’s” legacy of spirits and truth-seekers. “Fujisaki” may inadvertently

find truth – but she’s certainly not looking for it. She’s come to

destroy, not to discover. Positioned in this fashion, “Hellevator”

invites reading as a “post-slasher” text in which violence becomes less

a means of reaffirming essentialist, patriarchal myths about power and

gender, and more a direct social critique.

“Hellevator” seems relatively unusual for a contemporary

Japanese horror film. Its gritty reliance on both emotional and physical

violence and claustrophobic mise-en-scene, seem more reminiscent of the

elemental violations at the finale of “Audition” or cyberpunk excess than

of “Ring’s” legacy of spirits and truth-seekers. “Fujisaki” may inadvertently

find truth – but she’s certainly not looking for it. She’s come to

destroy, not to discover. Positioned in this fashion, “Hellevator”

invites reading as a “post-slasher” text in which violence becomes less

a means of reaffirming essentialist, patriarchal myths about power and

gender, and more a direct social critique.

It may be instructive to make brief comparison

with another cinematically impressive, well-acted, modestly budgeted production

that is unabashedly a contemporary slasher – the 2004 French film “Haute

Tension” (“High Tension”). This brutal film has many comparable elements

to “Hellevator,” including a female protagonist pushed to violence, small

cast, enclosed spaces, abject suffering and bloodletting, foreshadowing

and playfulness with time. Although the main protagonist in “High

Tension” is presented as delusional – as is “Fujisaki” – this is conflated

with her sexual orientation in a manner that codes her as inherently and

inexplicably monstrous. By contrast, although “Fujisaki’s” actions

may be monstrous, they are given context by presentation of a backstory.

“Hellevator” presents its female protagonist’s insanity and violence as

the product of patriarchal violence and oppression, whereas “High Tension”

treats its female protagonist as a decontextualized, incomprehensible threat.

It may be instructive to make brief comparison

with another cinematically impressive, well-acted, modestly budgeted production

that is unabashedly a contemporary slasher – the 2004 French film “Haute

Tension” (“High Tension”). This brutal film has many comparable elements

to “Hellevator,” including a female protagonist pushed to violence, small

cast, enclosed spaces, abject suffering and bloodletting, foreshadowing

and playfulness with time. Although the main protagonist in “High

Tension” is presented as delusional – as is “Fujisaki” – this is conflated

with her sexual orientation in a manner that codes her as inherently and

inexplicably monstrous. By contrast, although “Fujisaki’s” actions

may be monstrous, they are given context by presentation of a backstory.

“Hellevator” presents its female protagonist’s insanity and violence as

the product of patriarchal violence and oppression, whereas “High Tension”

treats its female protagonist as a decontextualized, incomprehensible threat.

This may illustrate an apparent point of divergence

between Western and Japanese horror narratives. Whereas many Western

horror films use narrative and subtextual codes to re-inscribe women into

a remarkably resilient patriarchal order, Japanese horror seems increasingly

dichotomized into egregious extremes of monstrous male behavior, and unexpectedly

brutal counter-violence by women. Even the ghosts that are Okiku’s

legatees crave vengeance. These films critique and subvert patriarchal

assumptions by speaking aloud when their Western counterparts remain discreetly

silent. In the end, when the monster is finally revealed, he may

well be a man dragging a pipe to batter one with as in Masayuki Ochiai’s

“Saimin” (“The Hypnotist,” 1999), or seeking to cut one’s heart out in

Ryuhei Kitamura’s “Sky High” (2003) – a metaphor for inevitable abuse and

betrayal. No matter how superficially charming, his power is ultimately

backed up by brute force, and must be equally violently confronted.

This may illustrate an apparent point of divergence

between Western and Japanese horror narratives. Whereas many Western

horror films use narrative and subtextual codes to re-inscribe women into

a remarkably resilient patriarchal order, Japanese horror seems increasingly

dichotomized into egregious extremes of monstrous male behavior, and unexpectedly

brutal counter-violence by women. Even the ghosts that are Okiku’s

legatees crave vengeance. These films critique and subvert patriarchal

assumptions by speaking aloud when their Western counterparts remain discreetly

silent. In the end, when the monster is finally revealed, he may

well be a man dragging a pipe to batter one with as in Masayuki Ochiai’s

“Saimin” (“The Hypnotist,” 1999), or seeking to cut one’s heart out in

Ryuhei Kitamura’s “Sky High” (2003) – a metaphor for inevitable abuse and

betrayal. No matter how superficially charming, his power is ultimately

backed up by brute force, and must be equally violently confronted.