Reportedly shrewd and business-savvy, Michiko seems to have consistently hedged her career bets. From her publicity as a body builder she evidently secured a variety of television roles, attaining celebrity status. This, in turn, facilitated the launch of her fitness gym business.

Securing even minor cameo roles in movies alongside some of HK’s greatest action stars guaranteeed exposure to movie audiences beyond the scope of her acting experience up to that point. Both “My Lucky Stars” and “God of Gamblers” had a Japanese connection, as well as lasting international appeal among fans of HK cinema. With such a sure career touch Michiko could have seemed destined for prominence in the HK movie industry.

However, several factors may have worked to

undermine this early success. In common with other industries, a “glass

ceiling” for HK actors during the late 1980s and early 1990s appears to

have been based on a combination of gender, nationality and sexuality,

in addition to distinguishing talent. Perhaps the most significant

of these was gender. Being female restricted access to certain roles

– especially action leads. It helped to be groomed by a studio or

perhaps have a relationship with an executive. It did not help to

be non-Chinese, or to have been identified with explicitly sexual roles

in a still substantially family-oriented film market.

Anti-Japanese sentiment has run strong in HK movies, reflecting both the painful military events of the 20th Century as well as subsequent economic and political tensions. Hong Kong cinema has often cast Japanese in marginal roles as either villains or sex objects, affording limited exposure and status. Few Japanese actors have achieved consistent prominence in the forefront of HK cinema. While at a superficial level this is consistent with film treatment of traditional foes – comparable to Hollywood’s view of Germans or Russians – a deeper fascination with the Japanese and their culture may also be discerned combining fear with admiration, frequently yielding stereotypes of Japanese fanaticism.

Consequently, it seems no coincidence that many of Michiko’s earlier appearances cast her as a villain and explicitly portrayed her as Japanese, often via the device of traditional, instantly identifiable attire. This is so for some of her best-known roles, including “My Lucky Stars” (1985), “Angel Terminators” (1990, the airport scene), “Magic Cop” (1990) and “The Real Me” (1991). In two other films (“God of Gamblers,” 1989 and “King of Gambler,” 1991) she was also clad in a kimono, but this time in the context of gambling. Even when Michiko was not traditionally attired, she could be paired with Yukari Oshima who had been so outfitted in “The Avenging Quartet (1993) while training as a revanchist Japanese assassin alongside men resembling WWII Japanese troops, or with a Japanese brother-in-law as the principal criminal character in “Raiders of Loesing Treasure” (1992). Her portrayal of a Japanese terrorist in “In The Line of Duty III” (1988) seemed inspired by the extremist Japanese Red Army. In approximately half her films she was either clearly cast as a Japanese in roles frequently pitted against the Chinese hero, or was identified with Japanese criminal, nationalistic or terrorist elements.

In fact, unlike their Chinese counterparts, both Michiko and the other principal female Japanese action actor in HK, Yukari Oshima, were each cast as terrorists. Where Michiko’s affiliation with the Japanese Red Army in “In The Line of Duty III” (1988) used murder and mayhem to procure cash for weapons, Yukari’s mission in “The Avenging Quartet” (1993) was to recover by any means an incriminating record of Japanese WW II war crimes against China. Consequently, the odium of both left- and right-wing political extremism was potentially associated both with recent Japanese history and these actors’ national origin. It is additionally noteworthy that both women’s actual names were used as their characters’ names in these two films – an apparently unique occurrence in their respective filmographies. Whether coincidental or deliberate, the potential for stigma by such prominent association of name and role seems evident.

Compounding this was the fact that in some

of her best roles Michiko played opposite some popular local favorites,

as their rival. Principal among these were Sibelle Hu (“My Lucky

Stars,” 1985), Chow Yun-Fat (“God of Gamblers,” 1989), Cynthia Khan (“In

The Line of Duty III,” 1988; “The Avenging Quartet,” 1993), Sharon Yeung

(“Angel Terminators,” 1990), and Moon Lee (“Princess Madam,” 1989; “The

Avenging Quartet,” 1993). The quality of the cast probably contributed

to her performance. By contrast, Michiko’s later leading roles tended

mostly to be in productions with less illustrious casts. Consequently,

her most memorable screen persona tends to be associated with earlier productions

in which she mainly played the villain.

Another factor appears to have been Michiko’s

screen character. Unlike her counterpart and fellow Japanese Yukari

Oshima, Michiko never developed consistent on-screen partnerships with

female co-stars that fueled the best GWG chemistry. Such distinctions

are even observable in subleties such as facial expressions – that played

a strong part in both these Japanese actors’ appeal. While Yukari’s

glares are mainly directed at what men do, Michiko’s glances tend to be

directed at the men themselves, bending them to her will. Michiko’s

screen chemistry was predominantly with men, while her physique and appearance

promoted seductive, femme fatale roles. But casting in this direction

obviously faced stiff competition, particularly when the challenge of learning

Cantonese and Michko’s distinctive accent and breathy voice tone are taken

into account.

Several of Michiko’s contemporaries were able to play relatively straightforward characters in a seemingly endless series of productions. It can be argued that the qualities that promoted their initial success – whether acting talent, martial arts skills or sheer looks – were also critical to sustaining it. For Michiko, early career success had seemingly relied on striking physical poses, only later buoyed by martial arts and range of acting. As this emphasis shifted, so did her parts. Her early femme fatale characters consumed males, and Michiko’s ability to project this power inspired some of her best roles. Unfortunately, roles as a leading character conventionally require more normal drives and appetites with which the audience may identify. Under these circumstances (“Passionate Killing In The Dream,” 1992; “Raiders of Loesing Treasure,” 1992; “Big Circle Blues,” 1993; “Whore and Policewoman,” 1993) Michiko’s performance was bound to appear relatively subdued and hence less memorable, due to adherence to familiar formulas. By contrast, in a reprise of earlier parts, Michiko seemed most natural as the over-the-top, exhibitionist femme fatale crime boss in “Hero Dream” (1993), surrounded by fawning men or cringing transsexuals. Here the combination of sexuality and violence is inherently transgressive, plunging the audience into a theater of power. Such explicit imposition of her will represents the essence of Michiko’s screen attraction. It’s a peformance not to be missed – but how often could something so extreme be repeated?

Michiko’s film career straddled both the upstart symbolism of GWG and guilty pleasures of gambling and Category III. To some degree her better acting performances have been overlooked in favor of those emphasizing style over substance. She was perhaps snared as much by her own physical appearance as was the audience, and when she had starred in the Japanese “pink” film “Young Lady Detectives” (1987) she already enjoyed celebrity status in Japan. However, subsequent apparent reticence about this movie perhaps suggested it was not necessarily viewed as a career asset.

When confronted by the relatively swift rise in HK Category III productions and correspondingly swift decline of GWG, Michiko appears to have hedged again by venturing into actioners with Category III elements. However, these hybrid Category III actioners proved equally short-lived, and the genre of female-centered action films – whether “girls with guns” or “femme fatale” appears to have been essentially played out by the mid 1990s, extended for a few years in the derivative Taiwanese industry. Michiko was among those who relocated in advance of the changes brought by 1997. Along with some of the stars or directors whose fame had originally secured her reputation, she now works in Hollywood.

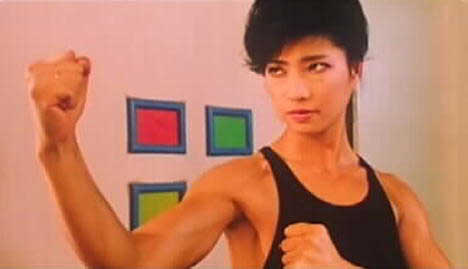

Perhaps alone among the female action stars

of HK cinema, Michiko accomplished the feat of appearing seductively sensual

without yielding an ounce of power and control. Her looks had served

both as a counterpoint to other female action stars, as well as passport

to explicitly sexual roles. In any state of dress or undress, Michiko’s

physique and costumes – combining Asian and Western styles and fabrics

with flair – create arresting screen images. With eyes like razors

and unpredictability ranging from sultry teasing to narcissistic cruelty,

Michiko’s edgy, dangerous characters define many of the movies in which

she appeared. Her powerful, passionate screen presence was refined

– but not defined – by her practice of martial arts. It is perhaps

a fitting compliment to note that while Michiko may have begun her movie

career modeling her physique and developed it by martial arts, by the close

she had achieved leading roles as an actor.